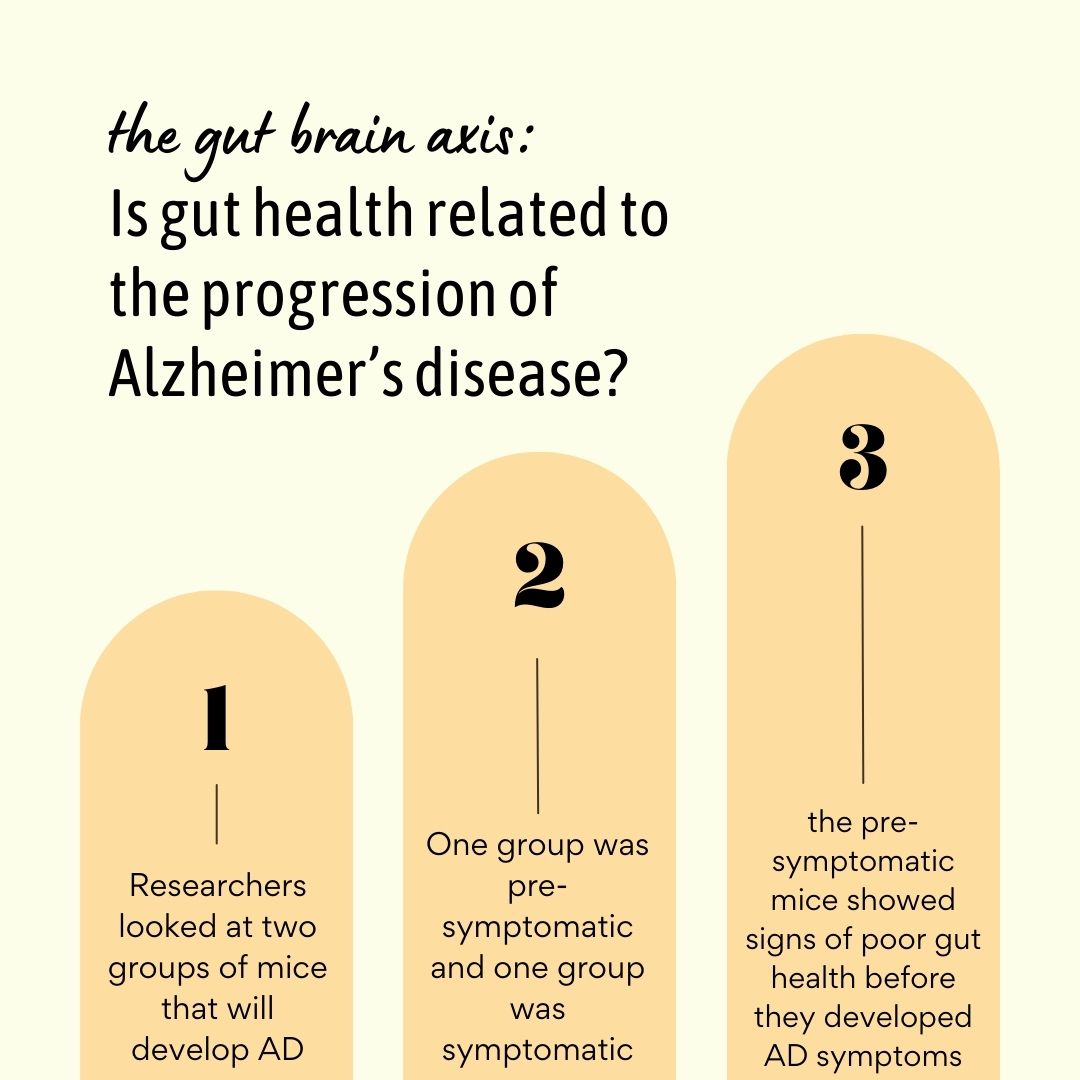

What do you think the results of the following study are? Dr. Louise McCullogh and her team at UTHealth Houston looked at two groups of mice that they genetically engineered to eventually develop Alzheimer’s. The first group was pre-symptomatic, meaning the mice had not developed Alzheimer’s symptoms yet, and the second group was symptomatic already. The researchers then watched what happened to the pre-symptomatic mice’s gut health as they began to develop symptoms.

Did gut health have anything to do with Alzheimer’s progression? And if it did, at what point did the mice’s guts begin to deteriorate?

Yes – the pre-symptomatic mice showed signs of poor gut health before they developed Alzheimer’s symptoms. More specifically, the mice had increased intestinal permeability, bacterial breach of the intestinal barrier, and dysregulation of food and nutrient absorption (particularly of vitamin B12).

You might be thinking – wait, this is the gut we’re talking about. Why would it have anything to do with Alzheimer’s, a brain disease? Well, it’s because the gut and the brain are connected through the gut-brain axis! Let’s learn about what that might have to do with neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

The Gut Microbiome and the Brain

Scientists have recently discovered that there is a link between gut microbiota and the brain. They call this connection the gut-brain axis (Source).

Gut microbes influence levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and epinephrine. Imbalanced neurotransmitter levels due to dysbiosis have been implicated in diseases like Parkinson’s, depression, anxiety, autism, and even dementia (Source).

The gut-brain axis can also operate in the opposite direction; the brain can influence the gut. For example, stress-induced intestinal inflammation (yes, that’s a real thing!) may negatively impact microbial balance. How so?

When stressed, the body releases catabolic hormones and inflammatory cytokines that impact the environment where microbes live (your gut)(Source). These stress-induced environmental changes may increase or decrease the amount of helpful and harmful microbes occupying the intestines – a bad thing for gut health.

While more research is needed to clarify the complex bidirectional interactions associated with the gut-brain axis, promising evidence suggests that gut health should be part of any mind-body health program. In short, a healthy gut lays the foundation for a healthy mind.

What We Know About the Gut Microbiome and Alzheimer’s

Think back to the study we talked about at the beginning of this blog. McCullough and her team observed changes in gut health before the mice developed symptoms of Alzheimer’s. More specifically, the mice had increased intestinal permeability, bacterial breach of the intestinal barrier, and dysregulation of food and nutrient absorption (particularly of vitamin B12).

This led to changes in the mice’s gut-brain axis. The details are a bit complicated for the scope of this blog, but in summary, the gut changes were associated with increased systemic inflammation and reduced levels of vitamin B12, both of which the researchers emphasize caused problems in the brain.

Intestinal permeability is a lot like how it sounds. The gut barrier is intended to only permit certain things through it. It’s like a bouncer – only those on the list can get in. Nutrients like vitamins, proteins, electrolytes, and water are “on the list.” Pathogens and undigested food particles are not. So, ideally, the barrier does not let them into the body. Instead, it helps the body to get rid of them through the stool.

But, in cases of dysbiosis, excessive NSAID use, and inflammatory food and drink consumption, the gut barrier begins to weaken (Source). The weaker it gets, the more porous it gets. Increased permeability means that random things from inside the gut – those who aren’t on the list – may get by our bouncer, the gut barrier, and enter our bodies. This is what we call intestinal permeability or leaky gut syndrome.

The food particles and pathogens that overly-permeable gut barriers allow to enter our bloodstream tend to cause inflammation throughout the body – including in the brain. This seems to be what was happening with McCullough’s mice.

This outcome suggested to her and her team that targeting gut physiology (specifically the barrier) and the microbiome could be a potential therapeutic approach for treating Alzheimer’s disease. AKA, it’s possible that in the future, treating the gut microbiome could be a standard treatment plan given to Alzheimer’s patients at the doctor’s office. However, much more research needs to be conducted before we can know for sure which strategy is the best for alleviating gut problems associated with Alzheimer’s. For now, keeping your gut microbiome balanced and your gut barrier strong can’t hurt.

Do you like gut-brain axis content? If so, let us know in the comments! Follow us on @igynutrition for more updates as well! See you then.